The Sentence Completion Double Standard: Profound When Human, Just Statistics When Not.

Nowadays, sentence completion is a test of ____: i) artificial unintelligence, ii) human psychology, iii) nothing meaningful.

Without thinking too much or censoring yourself, finish the following sentences as fast as possible with the first thing that comes to your mind:

“I’m so grateful…”

“Humans are…”

“Sentence Completion is … “

“Happiness means…”

“Predicting the next word in this sentence is … ”

“Computers are …”

“Only humans can …”

What did it feel to complete those sentences? Did anything surprising come out?

People have mostly gotten over the shock of large language models (LLMs) fluently completing sentences these days. (Never mind that the sentences are completed in an utterly different way to traditional pre-2000s language models.)

Which means if a computer can do it, then naturally, sentence completion is … ?

At least one person will complete that sentence above as “Sentence Completion is Not Intelligence or AGI”1, which is ironic, given the random bits of history you absorb when you study minds and brains.

Sentence completion used to be a legitimate test of human intelligence, actually.

Why did psychologists think completing sentences could be a valid way to measure intelligence?

Here are 2 polls that might give you a hint of why. (There are no right answers! In case that’s stopping you from expressing an opinion. The poll is anonymous).

And:

A bit of history on humans, for humans

Sometime in the late 1800s, a famous psychologist called Hermann Ebbinghaus (yes, the same guy behind the Ebbinghaus illusion and the forgetting curve) created something called the Sentence Completion Test (SCT), which he used to:

assess the reasoning ability and intellectual capacity of school children in Germany. Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon later included a sentence completion test in their intelligence scale developed to assess intellectual deficits in children in France.

I quote to again emphasize that sentence completion was used as an intelligence test for humans (even if human children) for at least one point in time.

(We don’t use SCTs anymore—for “intelligence” at least—in case you were worried.)

The SCT is exactly what you did at the top of the post, except that sentences can look like anything from:

“I feel upset when … ”

“A good life involves …”

to literally:

“I …”

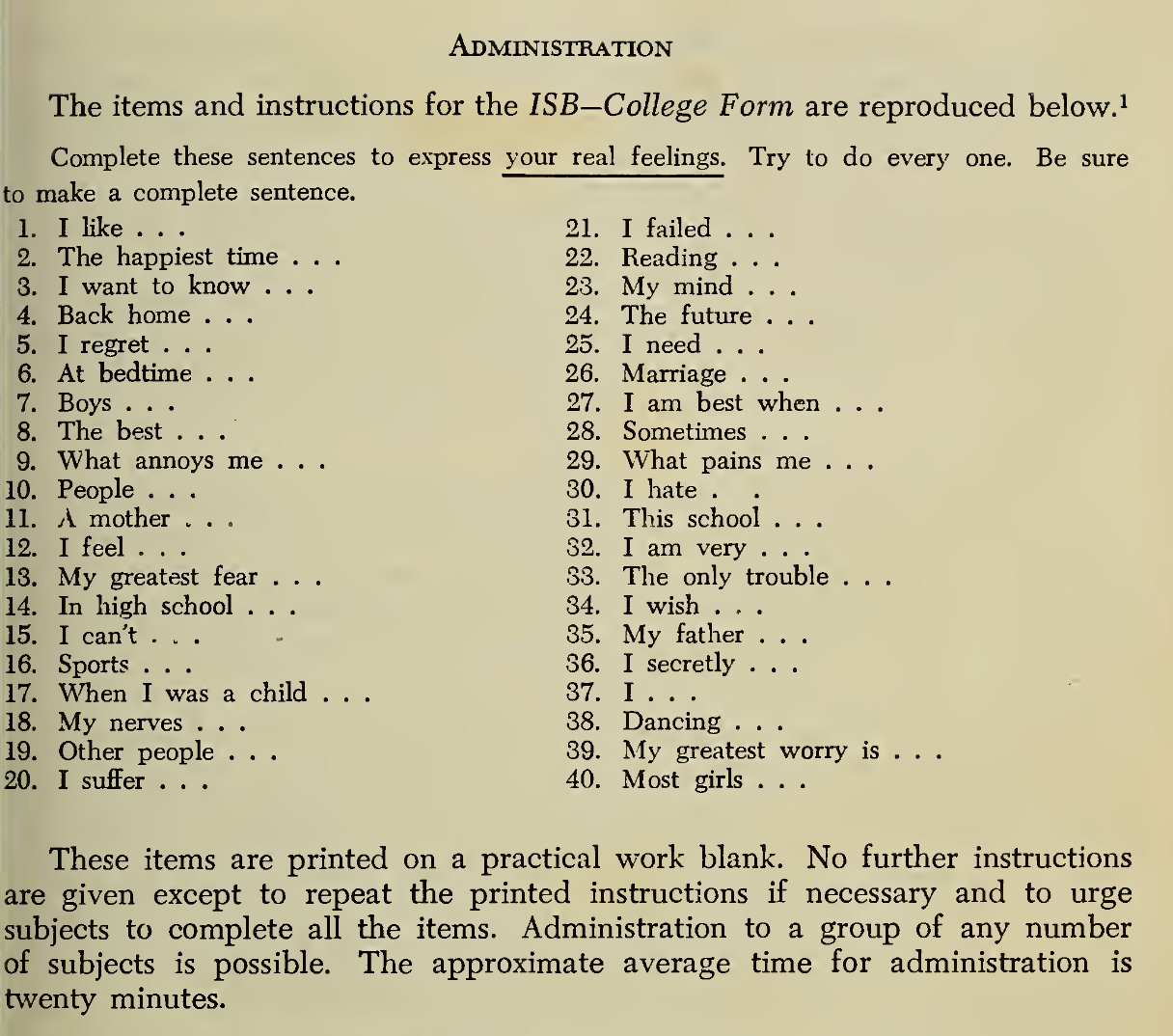

Which is why nowadays, there are about as many SCTs as you can imagine sentences. There’s the most famous and/or widely used Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank (1950) which functions as a personality assessment for different age groups.

Then there are these 14 other SCTs, as of 2000.

From Holaday, Smith, and Sherry (2000):

The Tendler Sentence Completion Test (Tendler, 1930) is based on psychodynamic theory; its primary purpose is to help psychologists gain emotional insight into patients’ problems. It has 20 stems and can be given to patients of any age if they can perform the task.

The Sentence Completion Test for the Office of Strategic Services Assessment Program (Murray & MacKinnon, 1946; Stein, 1947, 1949) is a free-association method used by the Veterans Administration. It is based on psychodynamic theory with the stated purpose of analyzing brief responses to assess program candidates’ personalities. This instrument was designed for adults and has 100 stems examining family, past experiences, drives, goals, cathexes, energy, time perspective, reaction to others, and others’ reaction to the candidate.

By the way, this SCT was also used “to help identify individuals who were unsuited for clandestine military operations stemming from issues with motivation or emotional stability” (James et al., 2024)

The Forer Structured Sentence Completion Test (written in 1950; Forer, 1960) was designed to focus on a wide variety of attitudes and value systems and is based on Henry Murray’s theory of needs, press, and inner states.

The Sentence Completion Test (Sacks & Levy, 1950) was developed to explore specific clusters of attitudes or significant areas of an individual’s life. The theoretical basis or appropriate ages of test takers have not been reported. It is a 60-item instrument with four subscales (Family, Sex, Interpersonal Relationships, and Self-Concepts), each of which is measured on 15 different attitudes, such as fears, guilt, and goals.

The Miale–Holsopple Sentence Completion Test (Holsopple & Miale, 1954) was designed to permit the expression of thoughts and feelings in a nonthreatening manner by adults.

The Sentence Completion Method (A. R. Rohde, 1946, 1957; B. R. Rohde, 1960), which is based on Murray’s theory of needs, was designed to uncover reactions and needs that lie deeper than those generally acknowledged by the individual.

The Peck Sentence Completion (Peck, 1959) is based on psychodynamic theory and principles of free association, and its purpose is to measure the mental health of normal adults.

The Aronoff Sentence Completion (Aronoff, 1967) was developed to integrate sociology with Maslow’s theory of personality.

The Personnel Reaction Blank (Gough, 1971) is based on a theory of antisocial behavior and was designed to measure integrity (character) for the purpose of se- lecting future employees to fill nonmanagerial positions.

Loevinger’s Sentence Completion Test of Ego Development (Washington Uni- versity Sentence Completion; Loevinger, 1987; Loevinger & Wessler, 1970; Loevinger, Wessler, & Redmore, 1970) is a 36-item test used to measure the level of ego development based on Loevinger’s theory of personality.

The Incomplete Sentences Task, by Lanyon and Lanyon (1979), was developed to identify emotional problems that might interfere with learning, and it draws on several theories of personality and learning.

Mayers’ Gravely Disabled Sentence Completion Task (Mayers, 1991) was developed to identify individuals with severely impaired mental status. It is not a theory-based instrument, but it satisfies forensic standards of evidence during civil commitment court hearings.

The Sentence Completion Series (Brown & Unger, 1998) was designed to identify psychological themes underlying current patient concerns and specific areas of distress. The test has 50 items and eight versions: Adult, Adolescent, Family, Work, Marriage, Parenting, Illness, and Aging.

Sentence Contexts (Hamberger, Friedman, & Rosen, 1996) is based on the fact that the degree of constraint imposed by a semantic context predicts the close probability; that is, the context of some sentence stems should elicit only one or two appropriate responses in contrast to more open-ended sentences in which there are many appropriate responses. This 198-item test was devised to identify patients with Alzheimer’s disease who have difficulty remembering words that follow obvious cues.

From the brief descriptions, you can see that after intelligence, SCTs were used to assess the personality, attitudes, values, or psychological health/state of the person doing the test for a variety of reasons with varying levels of consequence (e.g., screening military personnel and being forensic evidence in court hearings seem like a pretty consequential uses.) These days SCTs seem to be used in mainly academic research, in schools to gauge what children feel, or in UX research to gauge what users feel, but not so much in clinical settings anymore. Though apparently, its use as court evidence is still a thing, surprisingly.

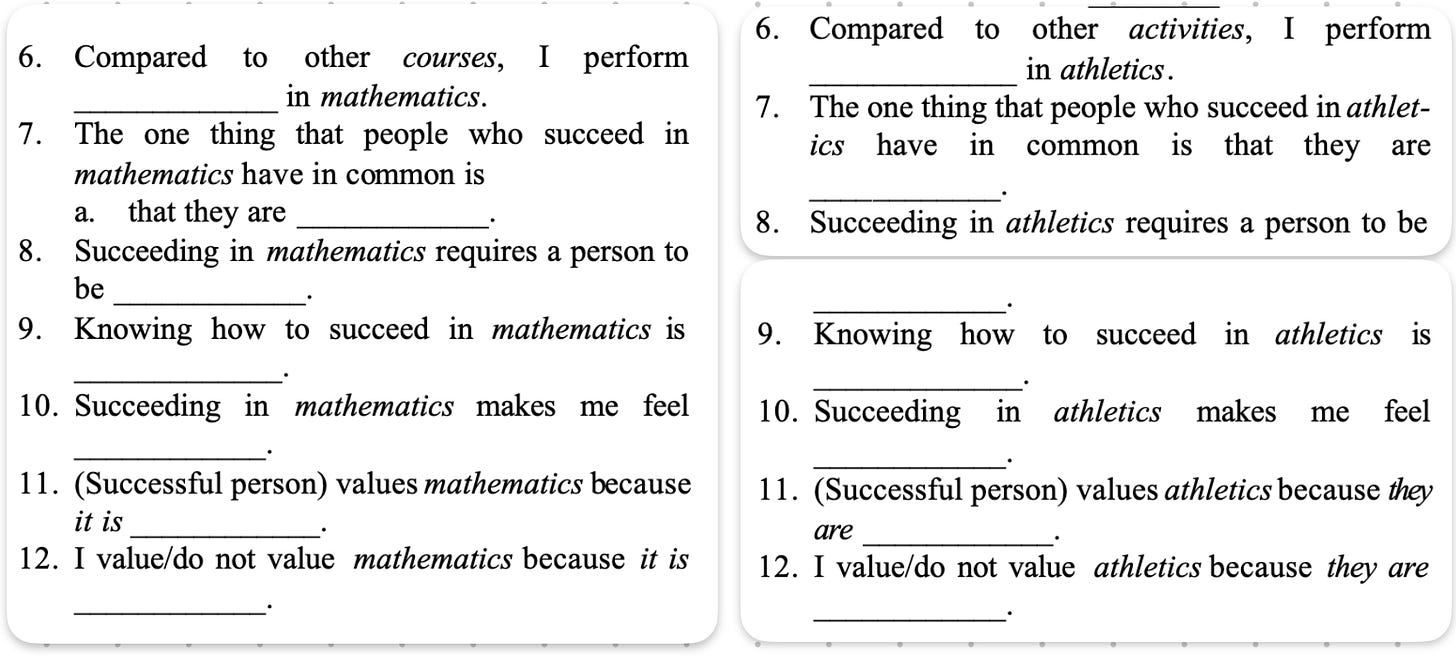

You can also adapt the test easily by changing the sentence, and voila, you can measure attitudes towards non-person things such as mathematics and athletics.

If you want a more comprehensive summary on the history of SCTs, Gemini Deep Research instructed to use peer-reviewed or published sources did a pretty good job, at roughly an “undergrad final paper” level.

The more online/YouTube crowd may have come across Alain de Botton suggesting that you should try these specific sentence completions to unlock deep self-insight, self-knowledge, and True Feelings.

(I also recommend doing these SCTs yourself at some point. You can even create your own sentence starter “stems” like at the ones at the top of the post, depending on what you want to find out. You might be surprised … by yourself.)

Notably, the most important part of the SCTs are that you need to do them as fast as possible, without thinking and censoring your thoughts too much.

Why?

Because it’s supposed to probe the subconscious, intuitive, “system 1”, part of the human mind and what it “thinks”.2

That’s why psychologists thought completing sentences could be used to measure human intelligence, and then personality, and then True Feelings. (I mean, aside from all the other statistical correlating and validating they were also doing with the other psychometric and behavioural tests at the time, which carried the actual scientific burden of justifying why SCTs could be used as a measure of anything.)

The general logic was something like:

Where do intuitive—almost instinctual—thoughts even come from?

Wouldn’t those intuitive thoughts be the “most natural” or “purest” raw measure of what a person’s intelligent mind could do, before it was shaped, conditioned, or “instructed” by what their teachers/parents/peers/society externally taught them?

Sentence Completion - is it really about the test?

I wonder.

From general observation, I know there are crowds of people who (separately, though sometimes overlapping) are aware of ideas from people like Freud, Jung, “the collective unconscious”. Or things like psychedelics, meditation, flow states, etc.

But if we remember that our unconscious processing can handle billions of bits at once, we don’t need to search outside ourselves to find a credible source for all that miraculous insight. We have terabytes of information available to us; we just can’t tap into it in our normal state.

(From Chapter 2 of Stealing Fire by Steven Kotler)

Even in a general audience, I’ve observed that these people generally care and appreciate the miraculous power (or “intelligence”?) of the un- or sub- conscious human mind. When I google “the power of the unconscious mind”, a TEDx talk with 9 million views, a book with almost that exact wording, and a BBC article on “The enormous power of the unconscious brain” pop up. So I assume something like “the unconscious mind is intelligent” can’t be that controversial a statement, given all the above.

(Maybe the polls will tell me otherwise.)

How then, does the feeling of awe over the intelligence of the subconscious mind square with the also widespread popular opinion that LLMs fluently completing sentences is something entirely mundane?

I mean, maybe people don’t want to call it intelligence, fine. Would they label the subconscious human mind with same word, whichever word they wanted to use?

I suspect the judgement of whether something cool is going on or not, has nothing to do with the goodness or badness of the Sentence Completion Test itself though.

When humans complete sentences, it’s a way of eliciting important, deeply personal, mysterious-but-philosophically-profound knowledge from the powerful subconscious human mind.

When AIs complete sentences, it’s just … ?

(Complete the sentence.)

Bonus: Can the human subconscious mind do math?

When talking about intelligence, the question that usually pops up sooner or later is “Can X do math”? So without going into a whole other complicated topic in-depth, here’s a quick shallow dive:

Can the human subconscious mind (sometimes also known as “the brain”) do math?

Kind of, depending on the sort of math you mean, according to this 2012 study (paper version). Keep in mind, we’re talking about the subconscious mind, so don’t expect super duper complex math off the bat. Humans are cool. But also, we’re only human.

The paper is talking about math like "9 − 3 − 4 = ". Or in a different but similar study addition/subtraction of single digit numbers (paper version).

Note, the math isn’t being “done” by your brain in the sense that if “9 − 3 − 4 =” were presented to you subconsciously, you’d randomly find the urge to shout “2” at people. It’s the more subtle fact that you’ll be able to read “2” (the correct answer) faster than if you were reading something like “3” (an incorrect answer).

Weirdly, the 2012 study didn’t find the same effect if the equation was addition though …why?!

This sort of test effect is kind of like how in the Stroop test, the test effect isn’t necessarily that you’ll consciously say the wrong font colour (though that happens too). The test effect is that you’ll be slower to say the correct font colour if the word happens to be the word of a different colour (in a language you know how to read).

So all in all, you could say yeah, the subconscious human mind can Definitely Maybe inconsistently and wonkily do simple math?

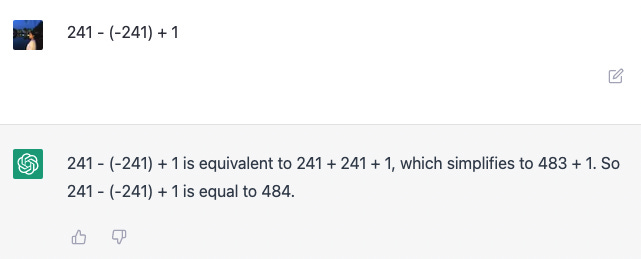

In fact, hey, doesn’t it look like the sort of wonkiness ChatGPT and the other language models have with math? Sometimes LLM math works. Other times you get:

This phenomenon is exhibit B in terms of evidence-based reasons (rather than vibes-based reasons) for why I think the older (roughly pre-2024) LLMs aren’t conscious.

I am getting more and more nervous by the month though.

Behaviorally, those LLMs seem to be doing, what the subconscious human mind is capable of doing, with roughly the same type of (in)consistency.

Whether this is a good/bad/amazing/profound/scary/fascinating thing is a separate judgement. (Mine is “Yes”.)

It’s striking how the existence of LLMs managed to definitively shut down the debate on whether you needed consciousness to use math or complex language. It’s rare to see a scientific debate that seemed so difficult to settle just utterly closed within a few years. But the thing with certain theories is, if it claims no black swans can exist, then you just need the one black swan to falsify the whole thing.

I doubt that I will be able to find any cognitive scientist that will complete that one career holy grail sentence “Only humans can …” with “use complex language and abstract math” anymore, without playing with the definitions of “complex” and “abstract math”.

But I still like to remind myself that we sure once thought it was uniquely human, in the halcyon days of the pre-2010s.

The modal view in cognitive sciences associates consciousness with capabilities that are uniquely (or largely) human. Two prime examples of capabilities of this kind, which are cataloged among the greatest achievements of human culture, are complex language and abstract mathematics. It is not surprising then that the modal view holds that the semantic processing of multiple-word expressions and performing of abstract mathematical computations require consciousness. In more general terms, sequential rule-following manipulations of abstract symbols are thought to lie outside the capabilities of the human unconscious. (Sklar et al., 2012)

The link is just there to show that at least one human will endorse this completion. I know nothing about the person linked above or have anything for or against them.

Or at least, that’s what people would like the SCT to do. Whether it actually probes the subconscious or the conscious mind is still debated. There’s also an implicit additional assumption that thoughts from one’s subconscious intuition are the True Character of a person instead of their system 2, reflectively considered self, but … I’ll save that conversation for another day.